So where does story come from?

Looking back on my work, novel number one, Off-Island, came from a desire to reach out to other women, perhaps men, who had been through the abortion experience and to offer a healing journey, neither Pro-Life or Pro-Choice, but a point of departure for discussion. With novel number two, Geraniums, the story wrote itself, but afterwards, I found in it a critical message: that at some point, no matter the age, the pressure, a person needs to speak up, tell the truth as they see it. In novel number three, Mine, the story blossomed from the first moment I beheld the beauty of my own infant son; the very first second I fell in love.

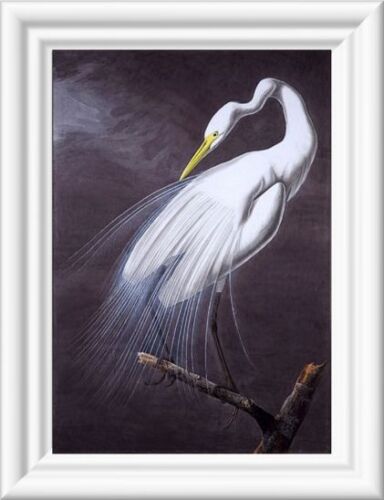

Novel number four, The Fair Incognito, grew out of almost forty years of trying not to write it. The story first “sparked” at the New York Historical Society with an oversized reproduction of John James Audubon’s Great Egret (1821), a watercolour that does not appear in his Birds of America. “No,” I shook my head, and took a step back, “I have zero interest.” But as I sat across from the image for the six weeks I served as a temp receptionist, the story started to attract me.

I had no idea of Audubon’s history, but more than the man, it was his wife that drew me in. Everything I read about her sounded a bit bogus, a bit inauthentic: ‘God-fearing,’ ‘charitable,’ ‘patient,’ ‘forbearing,’ etc. What she went through on the receiving end of an egotistical, self-indulgent genius can’t exactly be summed up in epithets such as ‘charitable,’ ‘God-fearing,’ etc. The more I discovered, the more I speculated that, without her (her backbone)—best guess—there would be no Birds of America.

In short order, having sold my Children of Alcoholics television project to CBS (broadcast in 1986 as Under the Influence), a time when I dreamt in three-act dramatic structure, the Lucy Bakewell story came all at once, and I thought, ‘Why not a film? And with the role of Lucy Bakewell for me.’

While seemingly farfetched, it turned out that my landlady in Westport, Connecticut was a descendant of the Bakewell family, Mill Grove (Audubon’s home) invited me to play the role of Lucy for the bicentennial of his birth, and the West Feliciana Historical Society and Museum in Louisiana was more than happy to serve as a conduit for the film’s fundraising. So I wrote Lucy’s monologue for the bicentennial, a synopsis and budget for the film proposal, but then took a long hard look at the road to actually raising money and selling the film.

I needed something more immediate to pay the rent, so I shelved Lucy, the development proposal and the acting career, saying no thank you (sadly) to the New Jersey Shakespeare Festival, where I had just been invited to take part. But happily Lucy via the Great Egret never gave up; she chased me down the years. You cannot imagine how many egrets appear on film, screen, bread wrappers, soaps, holy things, out my window, even manifesting in the flesh whether over Interstate 40 outside Conway, Arkansas or a wetland in the Baltics near Tallinn—not to mention my very own deck on the Oxford canal. ‘What about me?’ the bird always seemed to ask, especially when I have wanted to give up.

Well, the long and short of it is that Lucy got me finally, and I hope I got her in The Fair Incognito. It is clear to me that the original thesis, the spark, remains the same: without her Jean-Jacques, as he was originally known, would probably have gone insane, and no illustrative avian plates would have been left to be admired—and they are admirable indeed! So hats off to Lucy Bakewell Audubon, who played her part truly, fully, and deserves recognition beyond the one plate her husband attributed to her, a male Swamp Swallow in a May Apple.

Wishing you as always a Merry Month of March, and the courage to follow your Great Egret, wherever she might lead.

Love,