Hi All,

To me, June means Father’s Day. FATHER’S DAY writ large, that is. With a bigger- than-life father like mine, who could ever forget it? What do you give a man, a large man, a military man, who definitely does not want socks, ties or golf clubs of any size or description? My father, Harry F., died in November of 2014 and is still remembered this month, even if not in the way he might like: deep sea fishing off la República de Panamá.

Like everyone’s father, he was a one of a kind, a one and only. What didn’t I learn from him? Hard to enumerate—bravery, humor, persistence, or at least agreeing not to quit before I was done. Friends sometimes say when referring to their dad, “He did the best he could.” I say it too, especially now that I have recognized maturity means finally giving up on the notion of an ideal, pain-free childhood, and certainly the pipe dream of a faultless father.

Relinquishing the idea of the “coulda, woulda, shoulda” sort of father, empowered me to allow myself sometimes to be average, okay, fallible. Adequate and moderate, including plain wrong sometimes, mistaken, clueless even, now felt good enough. Everyone, it seems, has parents who have parents who had parents, ad infinitum, with their own morals, values and ideas about how to navigate this sometimes bumpy, sometimes not, road of life. No one has a rulebook for this, especially not for the bit called parenthood, and who, after all, ever gets that exactly right? This rough nugget of tenderly acquired wisdom let the jigsaw of my own childhood fall into place for me. Everyone is perfectly imperfect, or imperfectly perfect.

My father dreamed great dreams—the recounting of them mostly more thrilling than the actual reality—and made it his priority to teach me, or anyone else for that matter, to live life fully, broadly, embracing almost every experience. And—yes!—that included threading a needle, something he learned to do in the US Navy, along with how to tightly roll clothes so they tucked neatly and wrinkle-free into an old, green duffel bag, before pulling the drawstrings tight. Among the many other life lessons he felt it important to pass on to me, was the warning to make sure you really know your friends.Because your life could depend on it.

“Just like deep sea diving,” my father would say, “you need to know who is on the other end of that line. Will he stick with you in an emergency, or will he cut and run? Your life hangs on it.” Apparently, contact between the diver and his diving buddy (the one on the surface—in the boat, I guessed) was made by a series of pulls on a literal lifeline.Surface to diver: one pull on the line—are you OK? Two pulls—stay put; three pulls—go down; four pulls—come up at a normal speed; five or more pulls—emergency, come up to the surface immediately. Diver to surface:one pull—I am OK; two pulls—I am stationary; three pulls—I am going down; four pulls—I am coming up; five or more pulls—emergency, bring me to the surface (no reply necessary). He made the concept of friendship seem easy—would they be there at the other end of that line?—but his frequently repeated advice always left me with an uneasy feeling: what if I didn’t really know someone until they actually did a cut and run? Dangerous.

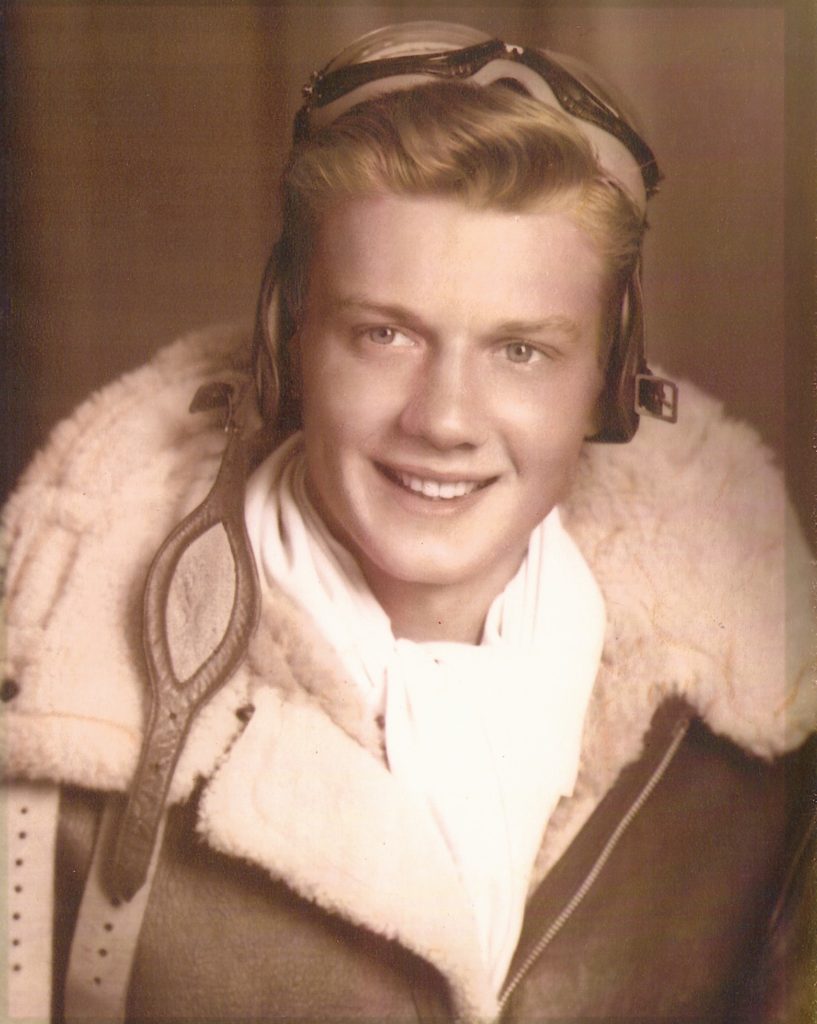

In the long and colorful story of my father’s life, at some point he made the move from seaman—his unique veins would not allow him to deep-sea dive or captain a submarine (apparently they might explode from the increase in atmospheric pressure)—to naval pilot and finally US Air Force pilot, when again those veins would keep him from being what he really wanted to do next: to be an astronaut. (Apparently being in space is another no-no for anyone with his particular vascular system.) Thank God, I thought upon hearing the news. With those same rolling veins and the see-through skin also inherited from my dad, I would never be required to hurtle into space or take a stroll along the seabed.

Being an Air Force pilot was where he found his happy place—not too crazily high-achieving but definitely not mundane. Enough. Out of the old photos he left me, the ones he had taken as a young lieutenant, I have a favorite. Inside the just-larger-than-a-postage-stamp, crimped border, the black-and-white image reveals tall, cumulus clouds, sheer and stark, seen from above—a pilot’s-eye view. Miraculous. Divine. A vista as seen by God. My dad’s Hawkeye Brownie Flash snapped this, but it is the words in indelible midnight blue ink, written in his strong, forward-slanting script, that complete the story: “Just another day at the office.”

Happy Father’s Day. Happy June,

Dear Marlene

Love you reflections – so full of great imagery – and the relational aspects of life.

I laughed at the references to being imperfect. I preached on that on Sunday touching on the title for the book I may one day write, “Fail Early and Often”. It left me free of trying to be perfect in (fill n the blanks…grades, attendance, etc.) and allowed me to be pretty normal and not drive me and all those around me crazy.

Tom