Hi All,

Change. Inevitable! Fear? Not!

Love at first sight? Actually, it was love just moments before—call it presight. First came the acres of sunflowers and soy and then, halfway down the miles-long drive, somewhere between the ancient stand of red eucalyptus (now gone, uprooted in the first tornado and finally demolished in the second) and the bend in the road where the birches (also now gone) shimmered silver in the bright morning light, I knew La Golondrina was mine.

At the end of the lavender-lined drive stood the sprawling casa principal, an inviting prospect with its terracotta roof tiles, white-washed walls, forest-green shutters, ornate grille-work and climbing red roses. Beyond the house unfurled a carefully landscaped, Europeanised vista, only hinting at the original scrub, elegant indigenous grasses and the vast expanse of Argentina beyond, with its romantic and tragic history, its rich soil capable of feeding the world.

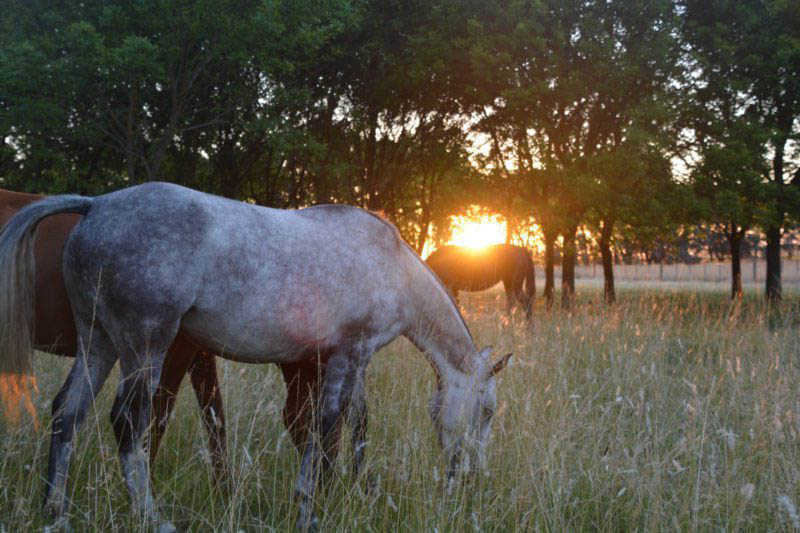

It’s been twelve years since I first saw the light flicker on those silver-barked trunks at the bend in the road. Like the vanished trees, the field where we first played polo and flew Chinese kites—long-tailed butterflies and wide-eyed dragons— is also a memory. Now waist-high in grass, fenced and used only for pregnant mares, it is the backdrop to the small chapel, where British men once sang a capella Christmas carols and La Virgen de Luján tumbled from her bier. Beyond the field a Mexican-style stable rises up, fantastical and unexpected, like a rogue wave in the middle of the pampa.

Clothed now in autumnal gold, the linden tree that was barely noticeable on that first day is now the hardest thing to leave. It took more than a decade to extend sturdy limbs over the crystal pool with its cascade of rock, surrounding cypresses and a hidden spring where swallows dip and dive. As with every other tree on the property, the incessant pampa winds have nudged the boughs southward towards the wild Atlantic—to the beach where fossilized sand carries the shallow imprints of saber-toothed tigers and other prehistoric creatures.

Audible on that unchanging wind are the mingled sounds of the men, women and children who came before me and who will come after—squeals of joy, playful splashing in water, a serenading guitar, voices singing, notes on a piano, the sizzle of an asado, chimangos calling from the skies, dogs barking, doors slamming, the threadlike cheeping of lost chicks, hooves thundering, cows lowing, arguments, fights, girlfriends, boyfriends, gossip, and wives quietly laughing. There is the scent of jasmine, roses, cana lilies, freshly mown grass and burning wood. A multitude of guests arriving—clients, family, friends, auction winners, tutors, cooks, cleaners. English, Argentine, Swedish, Dutch, French, Swiss. The clink of wine-filled crystal, silver, porcelain and glass… Señora, Señor, más? All borne on the wind.

La Golondrina means ‘the swallow’. It is also slang for ‘foreigner’, and a term once used particularly of migrant labor that would come and go. As I come and go, like so many others on the estancia. There is one particularly insistent guest whom I still unexpectedly see sometimes, here or there, catching a glimpse of him out of the corner of my eye. His arrival years ago was expected, but the subsequent returns were not. He arrived leaning heavily on doorframes, the bird dog and his wife. He seemed ready at any moment to give in, topple over for good. He slept sitting up and his face looked shocked and pale. After moving gingerly from one spot to another, he finally claimed the high-backed rocker on the galleria facing towards the chapel, the river, and the first fingers of night in the western sky.

Little by little this guest’s face, like every other visitor’s, tanned to a healthy shade, and he dropped his walking stick; even ran the dogs. In the pool, amazed to find himself there, he floated on his back, and at supper asked for más—wine, chocolate, pillows. In Spanish, he asked for walnuts, tea, and what time again was lunch? Finding one raven-haired helper more attractive than the rest, he explained to her that his gift of bougainvillea, planted by the chapel and the stable, would last forever, the way that love does. Like every guest who visited us, he didn’t want to go home. And in a way he never did. Sometimes love can even raise the dead…

Before they depart La Golondrina’s guests usually linger for a while at the shallow end of the crystalline pool, by the cascading spring—not wanting to abandon this Shangri-La, but knowing it’s time. The odd swallow dips and dives past them on the surface of the water. After some quiet reflection they will cock their heads to the sound of distant hooves drumming in the field; draw in the inviting scent of wood burning under the grill. Time to eat, time to leave.

Change. Nothing to fear.

Feliz Pasqua,